Our Heritage Revisited

Where The Man Is Buried In The Rock - "The Worms Crawl In, The Worms Crawl Out, The Worms Play Pinochle On Your Snout."

The second earliest forerunner (1810) of what’s now known as “The Hearse Song” is an 1810 nursery rhyme: “… On looking up, on looking down, she saw a dead man on the ground; and from his nose unto his chin, the worms crawled out, the worms crawled in.” One wonders if the young man we write of in this article (b.1817, d.1845) may have known the nursery rhyme and …

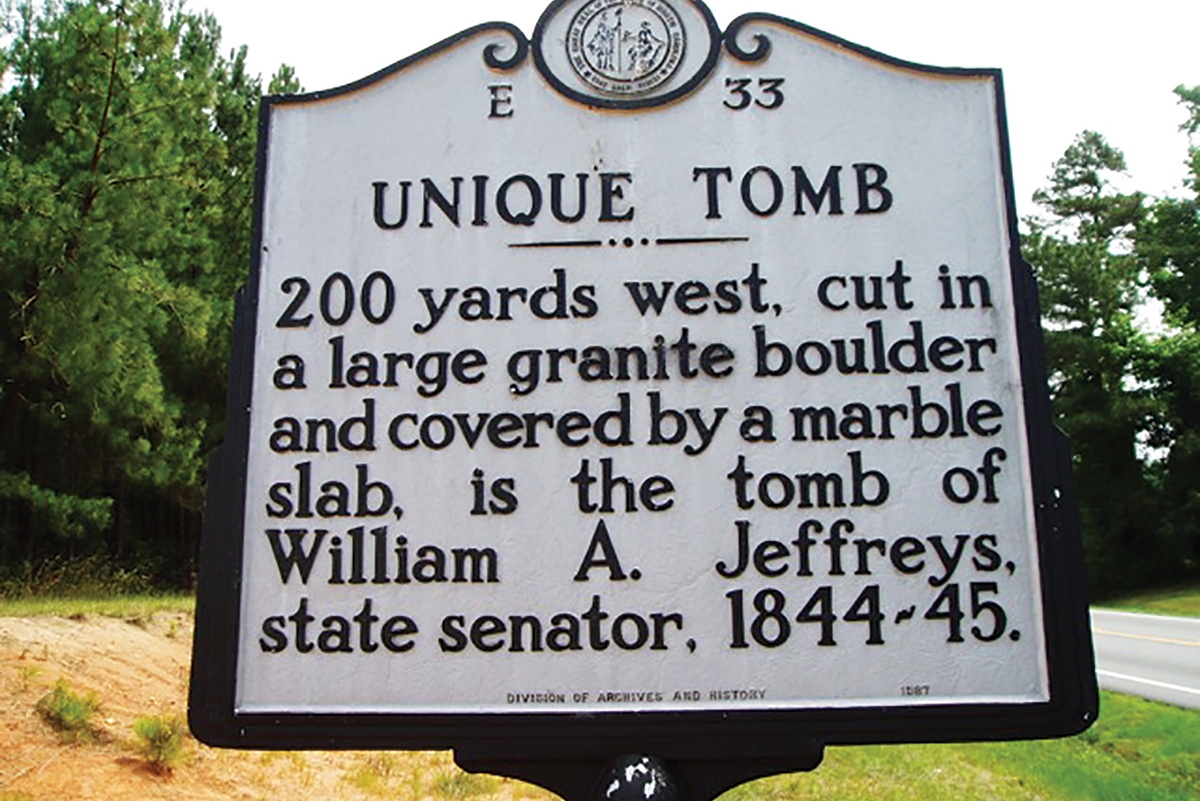

For this issue’s “Our Heritage Revisited,” we turn to two historical articles, one from the late T. H. Pearce, “Unique Tomb,” written for the 100th Anniversary Issue of The Franklin Times (1970), and the other, “Unmarked, Senator’s Rock Grave rests in Peace,” written by News & Observer staff writer Josh Shaffer (January 2, 2012). The subject of both men’s attention is the unique tomb of Senator William A. Jeffreys, and the reason this distinctive resting place exists at all.

The News & Observer article began with the following: “Weak, feverish, hours from death, young state Sen. William A. Jeffreys begged his family not to bury him in the cold, wet clay.

He pleaded from his sickbed for a sturdy grave, a resting place carved inside a 20-foot boulder on his family’s Franklin County farm, safe harbor from worms.” Pearce’s version is similar: “County legend has it that young Jeffreys had always expressed a horror of being buried in the ground. Following his son’s wishes his father had his body placed in a vault while his unusual tomb could be prepared. …

“Legend also has it that the young man’s body was preserved in brandy until the arduous task of chiseling his final resting place in the granite boulder was completed, but whether this is fact or fiction has been impossible to determine. It is fact, however, that the tomb was finally completed and young Jeffreys remains placed therein, the opening being sealed with a marble slab.”

The one-term legislator died in the 1845 typhoid fever epidemic, too early in his career to have become distinguished. In Franklin County, however, lore surrounding his final resting place has certainly provided notoriety for the young man whose tomb inscription describes “… a kind husband and parent, an honest man and an able and faithful public servant.” Few would have known about the young lawyer, so afraid to turn to dust within the ground, had the N.C. Historical Marker Program not erected one of its distinctive silver and black signs in 1942 along Highway 401. As Shaffer tells us, “The only reason he merited a highway sign in the first place was an ancestor who worked at the N.C. Office of Archives and History who nudged his name into distinction in 1942. It was a different world in the 1940s. People really used to go gaga over this kind of thing. Two years before the marker went up, a Canadian named Albert Legnini stole a mail truck in Raleigh and drove north to gawk at Jeffreys’ boulder, fulfilling a lifelong wish. He later explained that he didn’t have a car and planned to bring the postal vehicle back after a few hours.”

Through the years, border disputes between Franklin and Wake have been important to the former state historic site. Pearce’s humorous and relevant account is worth attention: “The fact that the tomb is located in Franklin County rather than Wake is a tribute to the uncompromising nature of

William Jeffreys’ grandfather, Osborne Jeffreys, according to the story handed down in the county. Sometime around the turn of the century (1800), surveyors were attempting to establish the boundary line between Wake and Franklin. When going across the Jeffreys’ holdings the line placed Osborne Jeffreys’ home in Wake County. This didn’t go over at all well with Jeffreys, whose family had been in Franklin since its beginning. As a matter of fact, the story handed down stated that Jeffreys got out his flintlock to help show the surveyors the proper location of the boundary line. The surveyors, being prudent souls, quickly decided that a flintlock in the hands of a determined and irate Franklin county man was much more accurate than their transits. The result being that the Jeffreys’ land was left in Franklin County.

“The Wake-Franklin line was in dispute for many years, with a half dozen or so surveys being made before it was finally settled in 1915. It is of interest to note, however, that present day maps show a slight bulge in the line, a permanent tribute to a resolute Osborne Jeffreys. It is in this light bulge that William Jeffreys’ unique tomb is located … known to Franklin Countians simply as ‘Where the man is buried in the rock.’”

The huge granite boulder, which took a Scottish stonemason an entire year to carve out, like many roadside attractions, took a little effort to get to – but not enough to keep out the “hooligans,” as Shaffer refers to those who smashed the marble slab atop the tomb. “Times, alas, have changed. ‘Jeffreys likely wouldn’t qualify for a marker today,’ said Ansley Wegner, a researcher with Archives and History. Being buried in a rock doesn’t really rise to statewide significance. The visitors that Jeffreys gets in the modern era tend to enjoy smashing things – his grave marker, for instance.” At the request of Jeffreys’ descendants, the state marker was removed in 2008. Locals, though, still know how to find the site. Despite the vandals, we hope that the long sleep of the man (and little boy he was) within his unique tomb has been a peaceful one.

Thanks to Deana Vassar and Joe Pearce; Kim Anderson and Michael Hill of the State Archives of North Carolina; Joe Shaffer and the News and Observer; and Martha Mason.

Amy Pierce

Lives in Wake Forest's Mill Village, where she is a writer, minister, and spiritual counselor.

- www.authenticself.us

- 919-554-2711