Our Heritage Revisited

Legacy, Legend, And Harricanean Reasoning ... The Harricane: Part One

Back in the day, if you asked someone in northwestern Wake County how to get to the Harricane, you’d invariably hear, “Oh, it’s just up the road a little ways.” They’d point, you’d tip your hat in thanks and head up the road. Before long you’d have to ask again, since by the time you’d thought, “Surely I should have found it by now,” you hadn’t. Now you’d hear, “Well, turn around and go on back down the road a few miles; you’ll come to it.” You might end up following the winding trail of this aspect of “Harricanean Reasoning” for quite some time before realizing that, truth be told, the Harricane just didn’t want to be found.

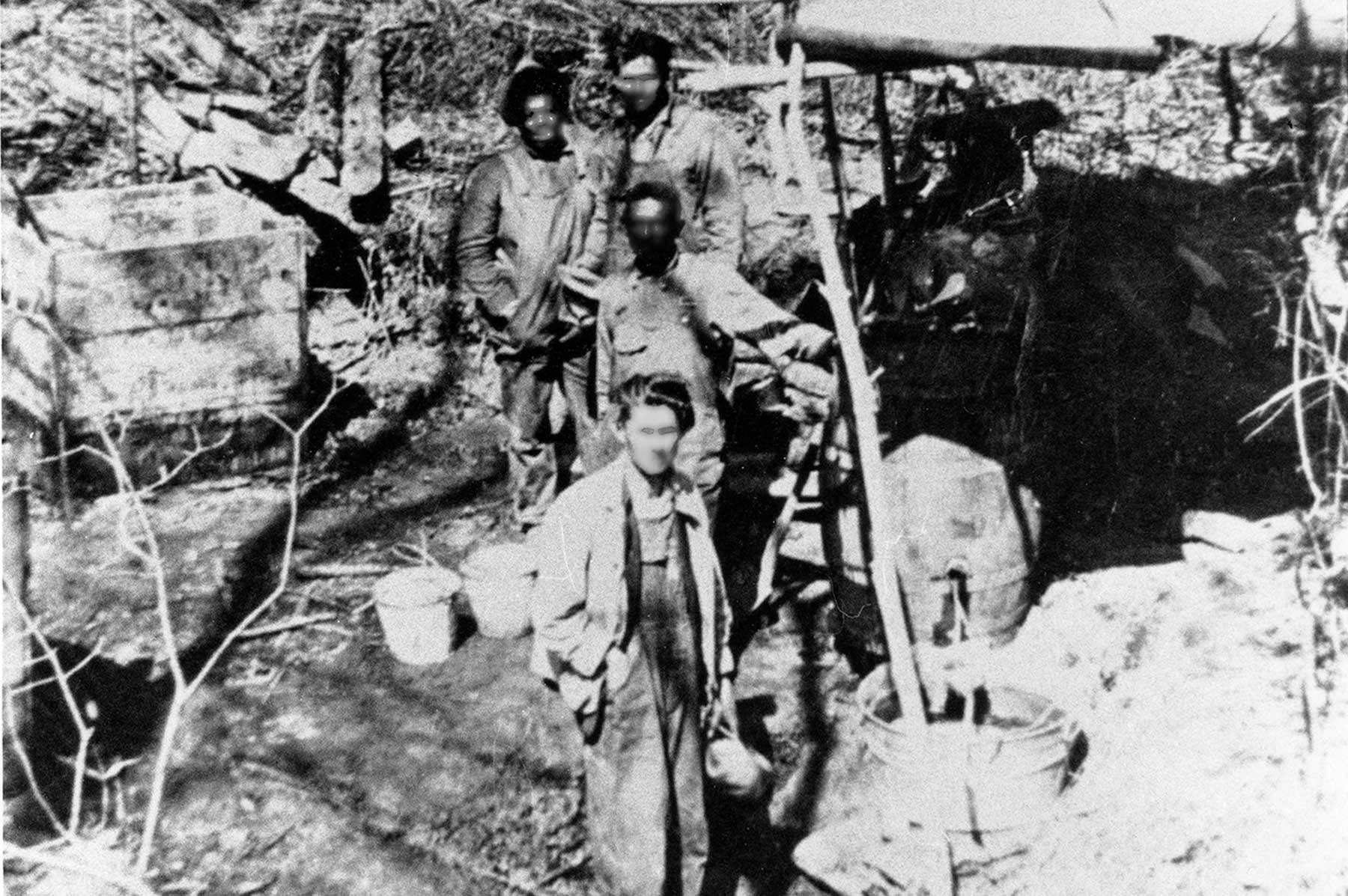

Both a place and a people, the Harricane held tightly to its identity and secrets, unless you lived there, in which case you knew it all – the families and their trials, the land’s leading hand, what it took to squeeze out a living – because you and the Harricane were of one mind, determined and guided by what Pete Hendricks calls Harricanean Reasoning: “Being practical and functional and working hard; having basic human ethics while doing the work you have to do to squeeze out a living that’s being forced on you by your surroundings.” For many families that work was, at least in part, the making of moonshine whiskey, which was how the very poor folks in Northern Wake County attempted to make a living during a very difficult time in our country’s history. Even with this hidden industry, many families lost their property because they didn’t have the money to pay the taxes.

Like the Neuse’s many creeks running through the region, Harricanean Reasoning runs through both the legacies and legends found there. The land and its own peculiar reasoning determined what sort of living it allowed those who settled upon it. They had to dig deep within and water the eternal seeds of human resilience, fortitude, creativity, and resourcefulness, from which their own crop of Harricanean Reasoning was harvested.

Located in the Upper Neuse River Basin, the intersection of Highways 98 and 50 is (or could be!) the geographical center of this area that extends east to old U.S. 1 (Wake Forest’s N. Main Street), north into Franklin and Granville counties, west to Oak Grove, and south into the Falls and Bayleaf communities. An old, handwritten note sent to former Wake Weekly columnist Pete Hendricks by a Harricane native may be the earliest account that could date the origin of the region’s name. It states that in August of 1830, the Wake County sheriff reported a storm came through the area “while they were barnin” [tobacco], and took up residence for a few days to tear up buildings, destroy crops, kill what livestock there was, and perhaps take human life.

In anticipation of this series, Pete and I drove west along winding, hilly, beautiful Purnell Road, looking for the Harricane. The brilliant hardwoods shone even brighter in the grey, misty morning. I asked Pete what it is that really characterizes the Harricane. “It’s the topography that makes it different, all the challenges from the hills and the soil. Purnell Road is typical of the whole, hilly region. In the early days, all the main roads (except Purnell) were built on ridges – Thompson Mill, Camp Kanata, New Light, though New Light does go through a creek bottom. “The political center was not in a town, but in the vast holdings out here, which existed without a real center except maybe Mr. Ray’s store near 50 and 98. Here you don’t have flat fields like you do below the Fall Line towards Rolesville. You have these hills, this convoluted clay full of rocks. The topography made these people land poor. Way up into the ’50s there were folks living here like people did back in the ’20s in most parts of the state.”

Scratching out a living on land akin to the Blue Ridge Mountains was hard, to say the least. Folks raised cotton and tobacco, though the land wasn’t good for either. Some of the larger holdings were profitable dairies. “While there are some small, fertile alluvial places good for farming, the money crops for most people had to do with growing grass, which you could turn into animal feed, or growing pine trees, which you could turn into lumber, or growing corn, which you could turn into liquor. Liquor was the quickest.” Harricanean reasoning led to their notoriety as moonshiners. Making whiskey was a necessity for many families simply trying to earn a living so they could pay the taxes and keep the farm. “Making liquor is killing work, the hardest work, because you have to secretly move thousands of pounds of material in and out of the still without anybody knowing about it, and you have the smoke from the fire to hide.”

Pete spoke of one of the community’s many little stores, a place he calls the sugar transfer point. “You’d go by and see this semi full of hundred-pound bags of sugar parked next to the store. The men would come in saying, ‘I need some sugar ’cause the wife is cannin,’ and then leave with 800 pounds of sugar for the damson preserves!”

Generations of Ryan Keith’s family hailed from northern Wake County. Delivering papers in the Harricane meant he came to know its people well. “They were wonderful folks. If they knew you, you wouldn’t find kinder people. As a child, I could never figure out why some of the outbuildings I went into were loaded down with bags of hog feed, big bags of Domino sugar, and brewer’s yeast! There were many honorable people out there making good whiskey. They didn’t use old radiators or lead solder, they just had nice little copper stills that made good moonshine. On the other hand, some folks made bad moonshine that poisoned people. I’ve also had it told to me that in the early 1900s when a revenooer went up into the Harricane, he never came back. I remember my father telling me that if I came upon a still when I was hunting to just turn around and walk the other way.”

Apparently, a still that you didn’t see, was a still that didn’t exist – and that’s one more example of the best of Harricanean reasoning! To be continued ...

Thanks to Pete Hendricks, Darin Ray, and Ryan Keith, who also provided our photo.

Amy Pierce

Lives in Wake Forest's Mill Village, where she is a writer, minister, and spiritual counselor.

- www.authenticself.us

- 919-554-2711