Our Heritage

We Built This: Wake Forest

The Wake Forest Historical Museum will host We Built This: Profiles of Black Architects and Builders in North Carolina, an exhibit created by Preservation North Carolina from April through July. We Built This highlights the stories of those who constructed and designed many of North Carolina’s most treasured historic sites, including Julian Francis Abele and Oliver Nestus Freeman. This exhibit explores pivotal moments in our history, including slavery and Reconstruction, the founding of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) and Black churches, and Jim Crow segregation.

Black men and women built some of Wake Forest’s most well-known and iconic structures, including the Calvin Jones House, the South Brick House, and the stone wall that encircles Wake Forest College’s original campus, now home to Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary and College (SEBTS). In bringing We Built This to Wake Forest, we hope to highlight the skill, creativity, and struggle of the Black craftsmen and women who helped build our community.

In 1835, Wake Forest College trustees hired John Berry, a builder from Hillsborough, to construct a new college building at the center of campus. Upon accepting the contract, John Berry relocated 10 to 20 enslaved laborers to the campus to complete the work. During the construction process, there was a fatal accident that claimed the lives of two enslaved African American men. Yet, few records document where their burials were.

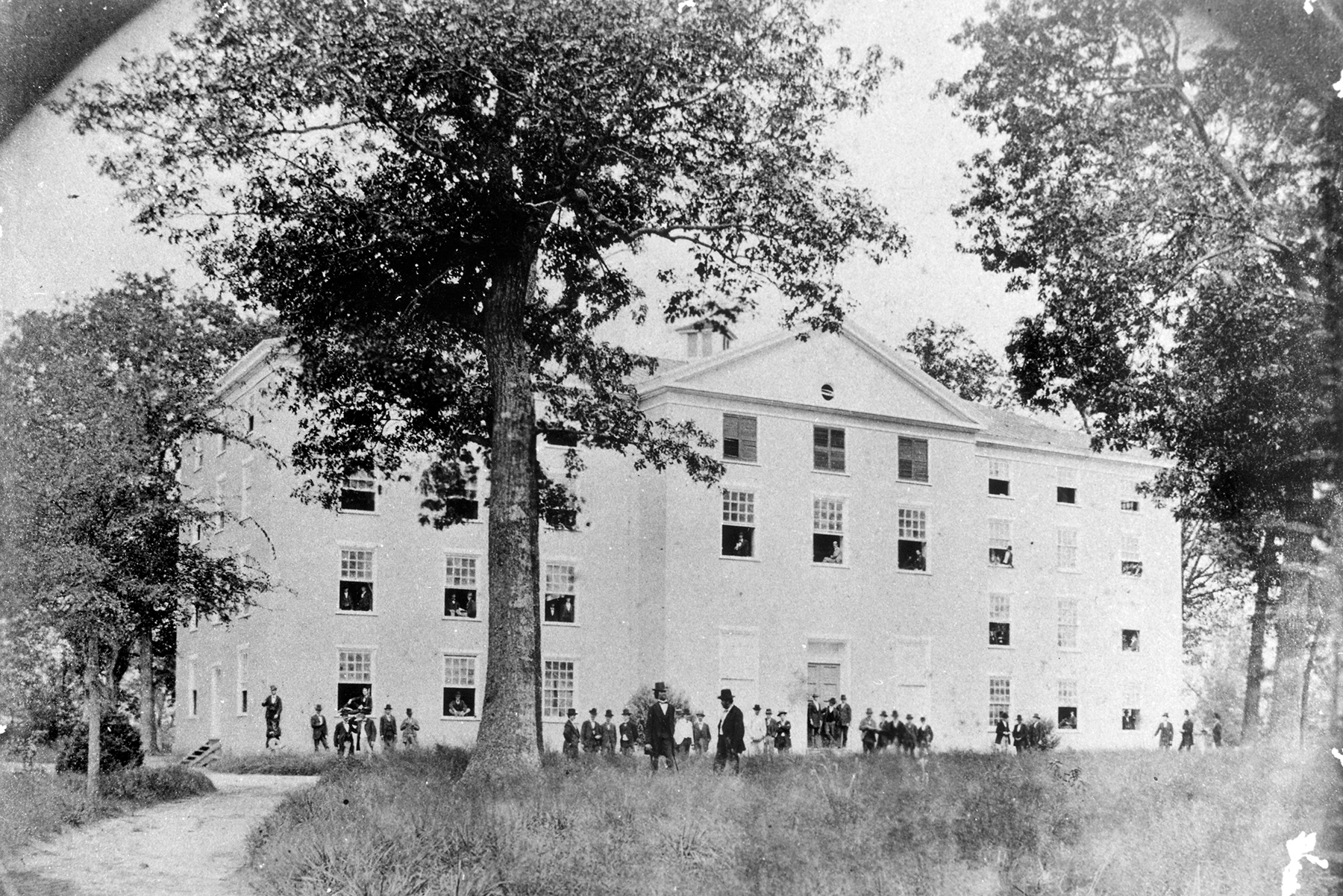

From 1835 to about 1840, enslaved men repaired or remodeled several wooden structures across the campus and constructed two faculty homes, including the South Brick House, which still stands today. The college building (pictured), later renamed Wait Hall, was destroyed by a fire in May 1933 and replaced by a new building.

Wake Forest College’s development continued as Thomas Jeffreys and Len Crenshaw built the stone wall (also pictured) that surrounds the campus. Thomas Jeffreys was born enslaved on a plantation in Mecklenburg County, Virginia, around 1846. After working as a tenant farmer in Virginia, he moved to Wake Forest around 1880. From 1884 to his death in 1927, he worked as a groundskeeper and janitor at Wake Forest College. Len Crenshaw was born into slavery at Waterfall Plantation, located to the west of Wake Forest. He and his parents, Allen and Lender Crenshaw, were enslaved by William Crenshaw, one of the original trustees of Wake Forest College. Len worked at Wake Forest College from about 1878 to his death in February 1890.

Beginning in the 1880s, Jeffreys and Crenshaw started the section of the stone wall on the east side of campus, facing the railroad tracks. This wall served as a physical boundary from the road to the campus and became a source of pride for students and faculty due to its aesthetic appeal. However, this pride failed to translate into adequate recognition for Jeffreys and Crenshaw. In 1934, students erected a plaque in honor of Jeffreys on the north side of campus for his service to the University. The plaque omits Jeffreys’ full name, Thomas Jeffreys, stating only “Doctor Tom.” There is no mention of Len Crenshaw’s contribution to building the wall.

To fully capture the architectural history of Wake Forest, it is important to recognize and honor the contributions of Black builders such as Thomas Jeffreys, Len Crenshaw, and the enslaved men who constructed the Wake Forest College campus. By acknowledging the labor and craftsmanship of those who physically built the structures, rather than solely attributing recognition to building owners, we can ensure that the legacies of North Carolina’s Black builders will not be forgotten.

Carolyn Rice

Manager of operations and external relations of the Wake Forest Historical Museum and Wake Forest College Birthplace.